Architecture of a Homemade Scientific Calculator

Posted: August 14, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentWith a lifelong fascination of pocket calculators, it was only a matter of time before I decided to code up one of my own. I have a tremendous respect for those early engineers  who were able to tease advanced mathematical functions out of underpowered early electronics, so I resolved earlier this year to write my own code for a pocket scientific calculator utilizing limited hardware resources. The result is SciCalc: a single-chip pocket-sized machine capable of performing high level math (such as trig and exponential functions), using the low-cost and low-power processor. This is the first of three posts to chronicle my experience, and what I learned along the way.

who were able to tease advanced mathematical functions out of underpowered early electronics, so I resolved earlier this year to write my own code for a pocket scientific calculator utilizing limited hardware resources. The result is SciCalc: a single-chip pocket-sized machine capable of performing high level math (such as trig and exponential functions), using the low-cost and low-power processor. This is the first of three posts to chronicle my experience, and what I learned along the way.

Technology Enablers

Prior to the invention of the microprocessor in the 1970’s, logic devices were capable of performing only the functions that they were designed to perform. In other words, any electronic device was designed from the start to behave in a well-defined, pre-ordained fashion. This approach had two principal shortcomings. First, the function of the device needed to be fully determined before anything could be created, which placed enormous demands on the hardware engineering team to “get it right the first time”. Once the designs were sent off to manufacturing, they were literally etched in metal to perform the pre-designed function. Second, any future changes, including even fixing errors (or “bugs”) required going back to the drawing board, changing the design of the basic circuits, and retooling the manufacturing process to accommodate the changes. This introduced significant risk, time and expense. As you may expect, the more complex the device, the more expensive these changes became. So early complex digital devices (such as desktop calculators) were loaded with expensive electronics, they consumed large amounts of power, and their cost was out of reach for most people.

However, in the early 1970’s a whole new philosophy emerged to counter this conventional design approach. With the introduction of the microprocessor, which originally targeted the calculator industry, relatively simple low-cost chips were created — chips now referred to as microprocessors. Microprocessors are digital circuits which have the ability to read “instructions” out of digital memory, and perform those instructions on the fly. This breakthrough enabled the engineering of simple hardware devices without having to predetermine how the device would ultimately behave. A set of logic instructions could be created and loaded into the microprocessor’s memory, essentially giving the microprocessor its personality. The same hardware could then be re-purposed, customized, fixed and enhanced by changing only the logical instructions in memory, without any physical changes to the hardware! This breakthrough essentially launched the modern computer age, and is how every smartphone, tablet and laptop works today; note how easy it is for you to download new apps for your smartphone over the air, giving it a whole new set of features! But long before smartphones, tablets or laptops, the basis of this approach was first utilized to create battery-operated pocket-sized calculators.

So in February 2016, I turned back the hands of time and set about the task of creating the code for a new scientific pocket calculator. But before writing the code, I had decide on a home within which the code would live. I needed a processor, and some buttons.

The SciCalc Hardware

Today, unlike in 1973, there is a staggering array of microprocessor choices from giant companies like Intel (the processor in your laptop), Samsung, and Apple (the processors in your phones). But these processors are much too powerful for this exercise. To put it in perspective, the original HP-35 scientific calculator utilized a one bit microprocessor, with room for 750 instructions. The processor in an entry-level iPhone 6 is a sixty four bit microprocessor, with room for sixteen billion instructions! Hardly a fair comparison. Of course the processors used in the early calculators are no longer available, but clearly the high-powered modern alternatives would have taken all of the fun out of the project. To replicate the feel of the good ol’ days, I needed a processor which had limited capability, and which would run for months or years on a single button cell battery.

After studying the available options, I decided to utilize an eight bit microprocessor from Atmel, a local silicon valley company. Founded in 1984, Atmel has built an entire company around simple, low-cost and low-power processor chips. The chip I selected has on-chip storage room for about 32,000 instructions (the ATmega328P chip). This is still more powerful than the microprocessors used to create early scientific calculators, but it has no where near the capacity of modern chips in our phones and laptops. It is also very frugal with electrical power, and if carefully programmed, should be able to stretch battery life to many months. One side benefit in selecting Atmel is that they also supply microprocessors for the extremely popular Arduino series, which means easy accessibility of prototype circuit boards and an off-the-shelf development environment.

So with the processor selected, I set about building an early version of my SciCalc software using the Arduino prototype board. The early versions of my code took input from a small off-the-shelf keypad. I began by writing the code to read the keyboard and drive the

display, then I built the simple calculator functions — add, subtract, multiply, and divide. Once I accomplished the basics I then got to work on the more complex functions — sine, cosine, tangent, square root, and exponential (I will spend more time on the math behind the techniques I used for these advanced functions in my next blog post).

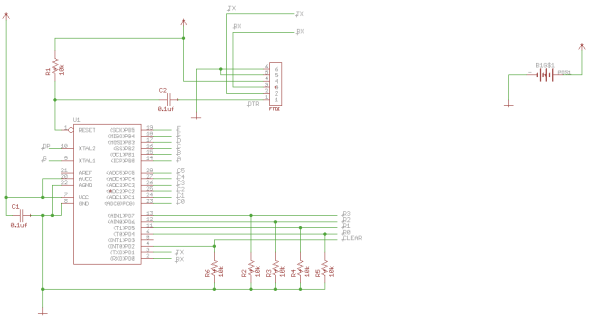

But beyond elegant math and intuitive operation, I was also interested in the physical design of the calculator hardware itself. After all, it was my love of the early Hewlett Packard scientific calculators whi ch led me here in the first place, and much of the appeal is in their industrial design — including their bright LED displays, tactile keyboards, and pocket-sized shapes. I clearly needed better hardware. Thankfully I found an excellent device: the Spikenzielabs Calculator Kit. Although it comes preloaded with minimal software, the hardware is fantastic. It includes a six digit LED display, 17 “clicky” keys, and it contains the same Atmel ATmega328P chip used by the Arduino (see processor schematic below). As it turned out, this is the perfect platform for my modern scientific calculator. As you’ll read in future posts, with some clever keyboard tricks and a few weekends of coding, I completed exactly the experience I had hoped for.

ch led me here in the first place, and much of the appeal is in their industrial design — including their bright LED displays, tactile keyboards, and pocket-sized shapes. I clearly needed better hardware. Thankfully I found an excellent device: the Spikenzielabs Calculator Kit. Although it comes preloaded with minimal software, the hardware is fantastic. It includes a six digit LED display, 17 “clicky” keys, and it contains the same Atmel ATmega328P chip used by the Arduino (see processor schematic below). As it turned out, this is the perfect platform for my modern scientific calculator. As you’ll read in future posts, with some clever keyboard tricks and a few weekends of coding, I completed exactly the experience I had hoped for.

Spikenzielabs ATmega328p Hardware Platform

(check out our personal website here: curd.net)

Designing a Scientific Pocket Calculator in 1,465 Easy Steps

Posted: February 12, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentAs a certifiable nerd, I have always had a fascination with pocket calculators. My first love was the “Bowmar Brain” calculator, which my parents gave to me for Christmas in 1975. I still remember my absolute amazement at entering “12345.6 x 7.89 =” and watching the glowing red display instantly flash the answer in eight glorious digits. How on earth could a tiny hand-held device contain so much magic! The Bowmar was only a “four-banger” in that it could only add, subtract, multiply and divide. However also during the ’70s Hewlett Packard had introduced the first true scientific pocket calculator — the venerable HP-35. Not only could this incredible pocket-sized machine do basic math, but it could actually compute high level scientific functions such as trigonometry, logarithms, and square roots! As unbelievable as it seemed, this little miracle was capable of these amazing mathematical feats from the palm of your hand, running for hours on three AA batteries. My family couldn’t afford the $400 it took to buy one of these in the 1970’s (the equivalent of $2,500 today!), but nevertheless I was hooked for life. This was the stuff of science fiction, and I wanted to be a part of it. What I did not understand at the time is that the innovation necessary to create these miracles would lead to the entire microprocessor revolution, ultimately laying the groundwork for every single PC, laptop and tablet computer in existence today, and not coincidentally, setting the stage for my entire career.

The key concept which made all of this possible is now known as “microcoding.” Instead of fixed, hard-wired logic which was pervasive at that time, microcoding enabled engineers to tell the machine what to do through simple logical instructions instead of physically connecting logic devices together. And these instructions could be changed relatively easily, essentially giving the hardware a new personality with each new program. This technique is very well-known now, but in the 1970’s it was an incredibly innovative breakthrough which enabled not only the creation of pocket calculators, but virtually every digital device in our lives today. Which brings us full-circle to my fascination with early calculators!

After studying some of the techniques used to create these pioneer calculators, I decided to re-create some of the magic myself. I wanted to personally experience what it may have been like to have been in that room in Palo Alto in 1970, when Bill Hewle tt turned to one of his young engineers, pointed to a massive desktop calculating machine, and said, “I want one of these things that will fit in my shirt pocket,” with no idea of how to accomplish it. I wanted to feel the joy of seeing my microcode causing red LED digits flicker to life; and watching the entry of decimal numbers as I tap buttons and watch them scan across the display; and more importantly, the struggle to coax advanced transcendental math functions out of tiny amounts of memory and computing power. To me, this seemed tantamount to building the Great Pyramid of Giza! So at the beginning of February I began dedicating a few weekends and several late nights to accomplishing this challenge — and what I learned was remarkable.

tt turned to one of his young engineers, pointed to a massive desktop calculating machine, and said, “I want one of these things that will fit in my shirt pocket,” with no idea of how to accomplish it. I wanted to feel the joy of seeing my microcode causing red LED digits flicker to life; and watching the entry of decimal numbers as I tap buttons and watch them scan across the display; and more importantly, the struggle to coax advanced transcendental math functions out of tiny amounts of memory and computing power. To me, this seemed tantamount to building the Great Pyramid of Giza! So at the beginning of February I began dedicating a few weekends and several late nights to accomplishing this challenge — and what I learned was remarkable.

Over the next few weeks I will blog about this experience, from start to end. I will begin with an overall design, touching on both the high-level organization of the microcode,  and strategies related to the hardware upon which the microcode depends. In the next installment I will share what I learned about the “user interface”: reliably reading keypresses and number entry, managing the LED display, and the surprising complexity associated with adapting the binary numbers used by the processor chip into a display readable by humans. And in the final installment, I will share my experiences learning how to perform high-level advanced math using estimation techniques developed in 1716!

and strategies related to the hardware upon which the microcode depends. In the next installment I will share what I learned about the “user interface”: reliably reading keypresses and number entry, managing the LED display, and the surprising complexity associated with adapting the binary numbers used by the processor chip into a display readable by humans. And in the final installment, I will share my experiences learning how to perform high-level advanced math using estimation techniques developed in 1716!

(check out our personal website here: curd.net)

MEMS and Me: How Does My FitBit Know I’m Walking?

Posted: August 25, 2015 Filed under: Research Leave a commentI am fascinated by the convergence of technologies to enable fundamentally new devices, and in some cases, even create entire new industries. Consider for a moment the iPad. Tablet computers are not the result of incremental improvements in existing technologies, but rather the convergence of dozens of radical innovations: high performance, low power processor technology; small, lightweight yet high energy batteries; ultra-high resolution LCD panels; capacitive touch screens; and miniature motion sensing chips (just to name a few). And when all of these innovations were brought together, supported by software, a brand new device was introduced which has revolutionized how we think about personal computing.

I would like to focus on just one of those innovations: motion sensing technologies. Because as it turns out, this is the innovation which enabled an entire fitness tracking industry.

In the past, you could have used a gyroscopic inertial guidance system to track your steps. For example, a state-of-the-art “micro” laser gyroscope from a decade ago weighed 10 pounds and consumed 20 watts of power (one example, shown here). Which means that to track your movement, you could have strapped this 10 pound metal box to your wrist, complete with a bank of AA batteries (which would have only lasted 6 minutes)!

from a decade ago weighed 10 pounds and consumed 20 watts of power (one example, shown here). Which means that to track your movement, you could have strapped this 10 pound metal box to your wrist, complete with a bank of AA batteries (which would have only lasted 6 minutes)!

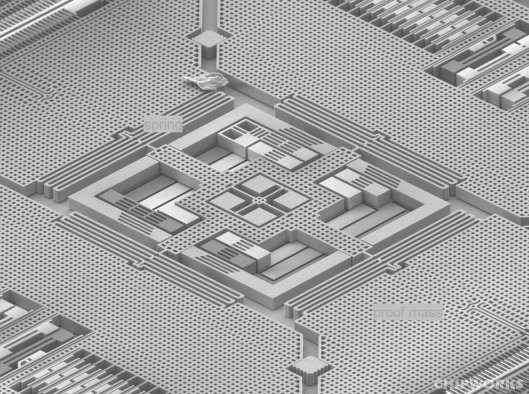

Thankfully that is no longer necessary. Today, a FitBit Flex weighs less than half an ounce, and the battery lasts five full days. Clearly one of the most important innovations necessary to achieve this weight & power performance is the motion sensor itself. Rather than strapping lasers and gyros to your wrist, today’s motion sensors are tiny and etched in silicon, much the way computer chips are created. Devices made in this way utilize an innovation referred to as “micro-electronic-mechanical systems”, or MEMS: essentially tiny, microscopic machines with actual moving parts, enabling the sensing of motion by consuming only tiny sips of power (the Flex seems to use a device from STMicroelectronics: data sheet here). Under high magnification, these intricate machines are stunningly beautiful (in a nerdy sort of way). The photo below is a scanning electron microscope image of the MEMS device inside your iPhone – for example, to sense when you tilt your phone to rotate the screen:

MEMS motion sensors (also known as accelerometers) rely on centuries-old physics which we all studied in high school science class: Newton’s First Law. Namely, “an object at rest stays at rest”. Inside of this little machine are all the elements necessary to demonstrate this on a tiny scale: a chip of silicon (the proof mass) suspended on miniature springs, with sets of interlaced fingers, or “capacitor plates”. These fingers don’t touch, however motion causes the micro springs to compress or expand as the proof mass attempts to remain at rest, which then causes the plates to move closer together or further apart. I created the below exaggerated animation to give you an idea of how this works:

Connected to a corresponding circuit, it is then possible to electrically detect the shifting distance between these microscopic fingers, and digitally translate those shifts into measurements of the motion. Now keep in mind that this entire motion-sensing machine fits in a chip barely bigger than a grain of sand! And they can be manufactured so inexpensively that you will find one in every tablet, smart phone… And now returning to the main point, every fitness band.

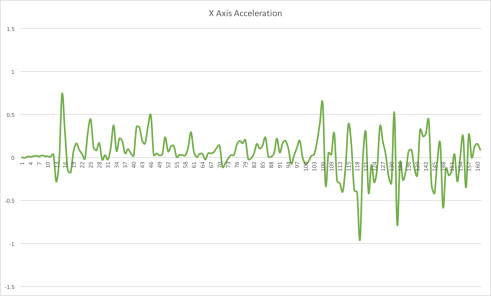

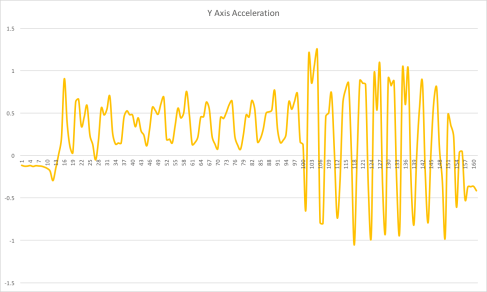

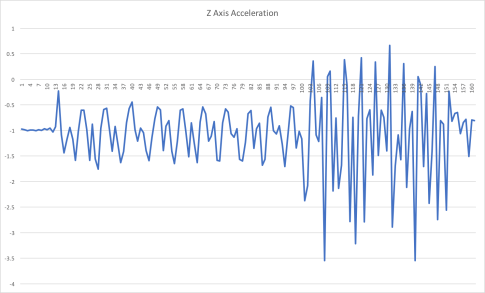

With a MEMS motion detector which has three of these micro machines to measure acceleration on each axis — x for forward or backwards, y for left or right, and z for up or down — all that remains to count steps is to apply some software rules to correlate these motions over time. To illustrate this, I hacked into the MEMS sensor in my iPhone (using an excellent application, techBASIC, which I highly recommend for my more technically-minded colleagues). I then held my phone in my left hand and ran a techBASIC program which measured motion in each axis (x, y, and z) 10 times per second while I took a little stroll with a couple of friends:

After crunching the acceleration numbers in Excel, I was then able to plot acceleration in each axis (you’ll see that about two thirds of the way across the graphs I started jogging, hence the bigger and more rapid waves):

With some smart software, not only is it possible to detect the periodic motion associated with my stride, but it is also possible to estimate exertion (due to the size and frequency of the waves), my direction of motion, as well as the position of the phone in space due to the force exerted by gravity! See how the blue Z Axis graph above hovers below the center line? This is caused by the downward force of gravity, or -1g (click here for the raw data).

Now when you strap that fitness band to your wrist, give a quick nod to the scientists and engineers who figured out how to create tiny machines on silicon chips, designed highly sensitive electronics to measure minute variations in distance, and wrote the intelligent software which can sift through these wiggling lines to count steps. (Usually even smart enough to figure out when you are trying to fool your FitBit by sitting still and flinging your hands about!)

So get up now, and go register some more steps.

(check out our personal website here: curd.net)

The Healing Power of Awareness

Posted: August 22, 2015 Filed under: Fitness, Healthcare 2 CommentsI recently acquired a Garmin VivoFit. I have no specific health risks, but I felt as a healthcare executive I should be practicing what I preach. I managed to dodge the first “FitBit Movement” — but have now jumped in, both feet first. By the way, this may also be a good time to admit that I am in my 50’s… Oh, and I just might be a few pounds overweight.

So I am now four weeks into my first fitness band experience, and bottom-line is that: it actually works. It really is that simple: I strapped this device on my wrist which (annoyingly) reminds me of how active I am, how active I should be, and whether I am getting enough sleep. I am exercising more, I am getting more sleep, and I am dropping a full pound a week! So let’s spend a few minutes exploring how something so inexpensive and so simple can be so effective.

Since the beginning of time, lack of awareness has been a first order factor in managing health and well-being. For example, at the turn of the century typhoid fever struck approximately 100 people out of 100,000 in the US. When it was discovered that typhoid was propagated by unsanitary water, municipalities undertook measures to begin sanitizing drinking water through chlorination. By 1920, the rate of infection had fallen to less than 34 people out of 100,000; by 2006, the rate was less than 0.1 cases out of 100,000 people (and 75% of those occurred among international travelers). The point is without an awareness of the source of the infection, it was impossible to solve this serious health problem. And conversely, mere awareness provided the clues which led to a simple solution. (click here for the raw CDC data).

As it turns out, my VivoFit is teaching me that my activity and weight management shortcomings are largely the result of my lack of awareness. I certainly didn’t expect to lose a pound per week, however my VivoFit (coupled with the easily integrated MyFitnessPal app) has made me much more aware of the duration of my sedentary periods, the additional calories I have been consuming through unneeded snacks, and my general level of activity. Keep in mind that I am not on a diet, I am not going to the gym, and we aren’t talking about quantum shifts in behavior here. Just natural, subtle changes in intake and activity, driven entirely by awareness.

In the future, I predict our level of health awareness will be significantly enhanced, far beyond simple motion and activity. Soon we will be able to track changes in our blood chemistry,  critical heart activity (e.g. AliveCor, which offers an EKG in a cell phone case for $60 today!), respiration, and pulse oximetry, all non-invasively and in real-time. We are just beginning to scratch the surface in terms of the power of awareness, in catalyzing each of us to live healthier, higher-quality lives.

critical heart activity (e.g. AliveCor, which offers an EKG in a cell phone case for $60 today!), respiration, and pulse oximetry, all non-invasively and in real-time. We are just beginning to scratch the surface in terms of the power of awareness, in catalyzing each of us to live healthier, higher-quality lives.

I’ll let you know how my fitness tracking ends up in the long run, but in the meantime I am encouraged. And even more motivated to pursue my professional passion of helping to keep people healthy through smarter technology, friendly user experience, and improved awareness!

Let me know what you think…

((check out our personal website here: curd.net)

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Posted: August 20, 2015 Filed under: Healthcare Leave a commentAs I have spent most of my adult life worrying about a single industry, I thought it may be helpful to describe, in my words, the framework of the US healthcare delivery system. If you come from a healthcare discipline, you may find this overview to be a naive oversimplification. But for the rest of you, I thought you may appreciate my attempt to demystify what is arguably the most important, and probably most complex, industry on earth.

As with most things in life, perhaps we can make the complex simple by separating this mega-industry into bite-sized chunks. Let’s examine the structure of the healthcare industry at the 30 thousand foot level.

Every healthcare event has the following components:

- Patient: ultimate beneficiary of the full set of services or products intended to aid recovery from an illness or accident, or to ensure optimal ongoing health

- Provider(s): the professional (or set of professionals) that render services, prescribe other procedures or products (e.g. prescription drugs), and collectively have accountability for the clinical result, or outcome. Providers are either individual professionals (e.g. physicians, nurses, physical therapists), or facilities (e.g. hospitals, radiology centers, diagnostic labs)

- Economic Payer(s): the entity (or entities) responsible for supplying the financial resources necessary to pay for the services and products delivered

- Payment Custodian: the entity which governs and manages payment to the provider

Note that some entities may adopt more than one role. For example, through co-pays and deductibles, the patient also becomes an economic payer. Additionally, in the case of an integrated delivery network, or IDN (such as Kaiser Permanente here in the West Coast, or Partners Healthcare in the Boston area, or Ascension Health in the Midwest), a single entity can simultaneously deliver the service, manage payment for the service, and provide the actual economic resources. In other cases, a self-insured employer (most large companies such as Bank of America, or General Motors) provides the economic resources for delivery of healthcare services but another third-party (such as UnitedHealthCare, or Aetna) is the custodian of the payments. So although the employer funds the services, a separate healthcare-savvy firm (third-party administrator, or TPA) manages disbursement of those funds — for an administrative fee. Another thing to keep in mind is that about half of all US healthcare expenses are paid by the US government, through Medicare and Medicaid programs (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS). And whenever CMS changes, the entire industry reacts.

Background: What’s Driving Change?

When all is said and done, the motivations and resulting behaviors across the healthcare industry are heavily influenced by reimbursement. In other words, whenever healthcare services or products are delivered, someone needs to pay. In a simple world, we would treat healthcare like any other business. If we were to get sick, we would visit a physician who would render his or her services, and we would get out our checkbook and pay the bill. Like changing the oil in our car, or getting our house painted. However, unlike an oil change, healthcare costs are far more difficult to anticipate. This can be true for single procedures (I will blog later on the topic of cost transparency), but it is also amplified by the fact that what may start as a single, simple procedure may result in a much more complex, much more expensive set of tests and procedures. So healthcare costs are often mysterious, hard to forecast, and they can be highly variable, ranging from a few dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars, or even more. It would be like dropping your car off at the dealer for a $40 oil change, and not learning until you pick it up the next day that they replaced your $6,000 engine instead! Furthermore, most business transactions have limited downside. In the case of your car, what’s the worse that could happen? If you do blow your motor and the expected repair bill is more than the car is worth, you salvage the car and purchase a new one. Certainly not a pleasant outcome, however it is still more palatable than being faced with a life-or-death healthcare treatment decision. With healthcare, there is no downside limitation, and your very life can be at stake.

To help buffer these dramatic variations, and the economic and personal risks associated with them, a concept known as risk pooling was introduced, or as we commonly refer to it, insurance. With risk pooling, a large number of people each pay into a common fund. As various members of that population then require healthcare services, money is drawn from that common fund as required. The theory is that many people will only require minimal and emergency care, therefore the amount they pay into the pool is more than the cost of their individual care. But offsetting this, others will require more care, and (hopefully) only a very few will require extensive (very expensive) care. So insurance is a way to distribute this variability risk across a large number of people, and to remove the potentially devastating economic “surprise” for the few unlucky folks that draw the short straw. Of course, a critical element when pooling risk is the calculation of the amount each individual needs to contribute. This is a very complex computation which considers the number of people contributing, and a clairvoyant attempt to forecast the future as it relates to how many people will become ill, how many will see a primary care physician, how many will visit a specialist, how many lab tests and radiology orders will be written, how many will suffer expensive and complex events such as heart attacks or cancer, and how many will be cost-free by “toughing it out” with over the counter medication and self-care. Our government payers (Medicare and Medicaid) represent roughly half the total medical spend in the United States, and those pooled medical expenses are paid by all taxpayers. The majority of the rest of the U.S. medical spend is borne by employer-based plans, meaning U.S. employers contribute to the risk pool. A much smaller portion is then covered by direct out-of-pocket and individual plan payers.

A fundamental challenge with this model is that most of us are wired to make individual decisions, not “good of society” decisions. As an example, if a loved one has a care need and an outrageously expensive treatment exists, we are likely to insist on providing that treatment, even if the treatment represents only a slight chance to resolve the problem. On top of this, health care providers are often paid on a procedure bases, or what is referred to as fee for service. In a fee for service world, the more procedures a physician performs, the more money he or she makes.

So healthcare finds itself wedged between a rock and a hard place. Most healthcare expenses are drawn from risk pools that are largely funded by taxpayers or employers. These pools are limited, yet the demand to draw from them tends to be practically unlimited. So something has to give.

Throughout the history of healthcare, various initiatives have been initiated in an attempt to somehow manage demand. The introduction of diagnostic related groups (or DRGs) in the 1980’s was an attempt to restrict hospitals by determining in advance how much they would be paid for each of the reasons people were hospitalized — hospitals no longer had a blank check. Patient co-pays and deductibles were also introduced, in an attempt to share some of the economic risk with the patient — “If I have to pay $25 to see the doctor for this cough, do I REALLY need to go, or can I wait to see if it gets better on its own?”. Then, throughout the 1990’s, the notion of health maintenance organizations (or HMOs) were implemented to manage cost by economically rewarding providers to avoid unnecessary care, as well as encouraging better coordination across all of the specialty providers to eliminate redundant serv

ices. Although these moves have all helped to some extent, the graph to the left proves that none of  them have solved the root cause issues of spiraling costs: as you can see, the spending per person on healthcare in the US (the top line) is significantly higher than healthcare spending in any other country. And what results do we get in return? According a study by a well respected foundation (the Commonwealth Fund: click here for more information), the US ranks dead last in multiple measures of healthcare quality among 11 countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Something is clearly and seriously wrong.

them have solved the root cause issues of spiraling costs: as you can see, the spending per person on healthcare in the US (the top line) is significantly higher than healthcare spending in any other country. And what results do we get in return? According a study by a well respected foundation (the Commonwealth Fund: click here for more information), the US ranks dead last in multiple measures of healthcare quality among 11 countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Something is clearly and seriously wrong.

The Affordable Care Act

With the passing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (or ACA) in 2010 (upheld by the US Supreme Court in 2012), ten new “titles” were introduced into law, in a sweeping reform of the US healthcare ecosystem. The intent of the ACA is to ensure that more people were covered through public and private insurance plans, to increase the quality and affordability of health insurance, and to reduce overall costs of healthcare for individuals and the government. In other words, to produce better health results while spending less money. But within that one sentence is the most impactful overhaul of the US healthcare system in 30 years. And with revolutionary change comes tremendous opportunity.

As a consequence, all of us in the healthcare industry are becoming more aligned to what really matters. Concepts such as delivering and measuring overall quality of the patient experience and outcome as it relates to the resources necessary to deliver that outcome (“Value-Based Purchasing”). And simultaneously delivering the trifecta of the (1) most positive patient experience, (2) ensuring better health of the total population, and (3) with reduced resources and cost (“Triple Aim”). Not to mention worrying about keeping people healthy from the start, and keeping them out of the healthcare system altogether!

So with a single stroke of the legislative pen, sensible concepts which should have been woven throughout the fabric of our healthcare system from the beginning of time have led to a rethinking of everything we have learned about delivering care. From my perspective, it is largely for the better, and it opens up tremendous opportunities for innovation that benefits all of us.

So stay tuned — I have made a personal decision to be on the front lines of this revolution in US healthcare delivery. As I join in the fight to rebuild this entire $3 trillion industry brick-by-brick, I will provide glimpses of progress and perspective through my blog. Please feel free to share your thoughts below. And hang on for the wild ride.

(check out our personal website here: curd.net)