MEMS and Me: How Does My FitBit Know I’m Walking?

Posted: August 25, 2015 Filed under: Research Leave a commentI am fascinated by the convergence of technologies to enable fundamentally new devices, and in some cases, even create entire new industries. Consider for a moment the iPad. Tablet computers are not the result of incremental improvements in existing technologies, but rather the convergence of dozens of radical innovations: high performance, low power processor technology; small, lightweight yet high energy batteries; ultra-high resolution LCD panels; capacitive touch screens; and miniature motion sensing chips (just to name a few). And when all of these innovations were brought together, supported by software, a brand new device was introduced which has revolutionized how we think about personal computing.

I would like to focus on just one of those innovations: motion sensing technologies. Because as it turns out, this is the innovation which enabled an entire fitness tracking industry.

In the past, you could have used a gyroscopic inertial guidance system to track your steps. For example, a state-of-the-art “micro” laser gyroscope from a decade ago weighed 10 pounds and consumed 20 watts of power (one example, shown here). Which means that to track your movement, you could have strapped this 10 pound metal box to your wrist, complete with a bank of AA batteries (which would have only lasted 6 minutes)!

from a decade ago weighed 10 pounds and consumed 20 watts of power (one example, shown here). Which means that to track your movement, you could have strapped this 10 pound metal box to your wrist, complete with a bank of AA batteries (which would have only lasted 6 minutes)!

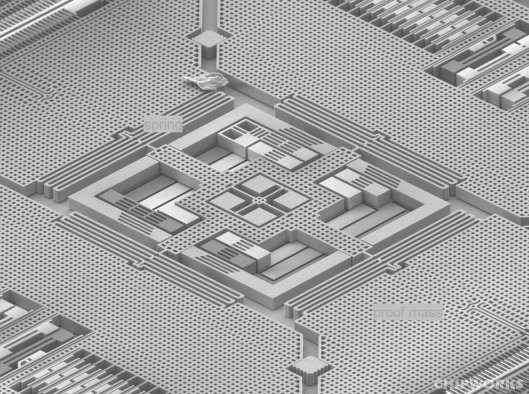

Thankfully that is no longer necessary. Today, a FitBit Flex weighs less than half an ounce, and the battery lasts five full days. Clearly one of the most important innovations necessary to achieve this weight & power performance is the motion sensor itself. Rather than strapping lasers and gyros to your wrist, today’s motion sensors are tiny and etched in silicon, much the way computer chips are created. Devices made in this way utilize an innovation referred to as “micro-electronic-mechanical systems”, or MEMS: essentially tiny, microscopic machines with actual moving parts, enabling the sensing of motion by consuming only tiny sips of power (the Flex seems to use a device from STMicroelectronics: data sheet here). Under high magnification, these intricate machines are stunningly beautiful (in a nerdy sort of way). The photo below is a scanning electron microscope image of the MEMS device inside your iPhone – for example, to sense when you tilt your phone to rotate the screen:

MEMS motion sensors (also known as accelerometers) rely on centuries-old physics which we all studied in high school science class: Newton’s First Law. Namely, “an object at rest stays at rest”. Inside of this little machine are all the elements necessary to demonstrate this on a tiny scale: a chip of silicon (the proof mass) suspended on miniature springs, with sets of interlaced fingers, or “capacitor plates”. These fingers don’t touch, however motion causes the micro springs to compress or expand as the proof mass attempts to remain at rest, which then causes the plates to move closer together or further apart. I created the below exaggerated animation to give you an idea of how this works:

Connected to a corresponding circuit, it is then possible to electrically detect the shifting distance between these microscopic fingers, and digitally translate those shifts into measurements of the motion. Now keep in mind that this entire motion-sensing machine fits in a chip barely bigger than a grain of sand! And they can be manufactured so inexpensively that you will find one in every tablet, smart phone… And now returning to the main point, every fitness band.

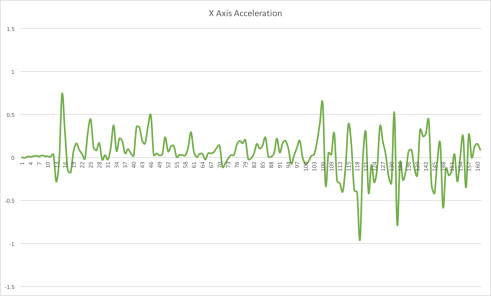

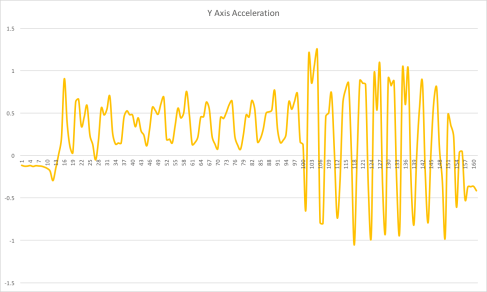

With a MEMS motion detector which has three of these micro machines to measure acceleration on each axis — x for forward or backwards, y for left or right, and z for up or down — all that remains to count steps is to apply some software rules to correlate these motions over time. To illustrate this, I hacked into the MEMS sensor in my iPhone (using an excellent application, techBASIC, which I highly recommend for my more technically-minded colleagues). I then held my phone in my left hand and ran a techBASIC program which measured motion in each axis (x, y, and z) 10 times per second while I took a little stroll with a couple of friends:

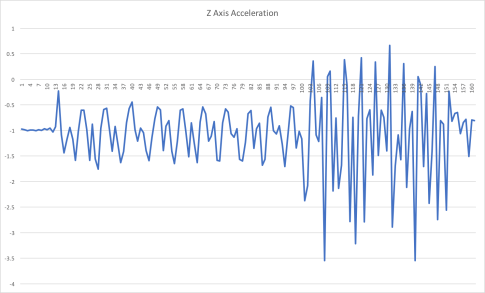

After crunching the acceleration numbers in Excel, I was then able to plot acceleration in each axis (you’ll see that about two thirds of the way across the graphs I started jogging, hence the bigger and more rapid waves):

With some smart software, not only is it possible to detect the periodic motion associated with my stride, but it is also possible to estimate exertion (due to the size and frequency of the waves), my direction of motion, as well as the position of the phone in space due to the force exerted by gravity! See how the blue Z Axis graph above hovers below the center line? This is caused by the downward force of gravity, or -1g (click here for the raw data).

Now when you strap that fitness band to your wrist, give a quick nod to the scientists and engineers who figured out how to create tiny machines on silicon chips, designed highly sensitive electronics to measure minute variations in distance, and wrote the intelligent software which can sift through these wiggling lines to count steps. (Usually even smart enough to figure out when you are trying to fool your FitBit by sitting still and flinging your hands about!)

So get up now, and go register some more steps.

(check out our personal website here: curd.net)